The Moon King’s Fall – How Do Kwon Built and Destroyed a $40 Billion Crypto Empire

He promised a decentralised utopia – a financial system based on cryptocurrencies, freed from the control of banks and governments, governed by elegant algorithms and the wisdom of crowds. He built one of the biggest scams in history. The story of Do Kwon and the fall of Terra and Luna – the cryptocurrencies ‘Earth’ and ‘Moon’ – is the most complete illustration of what the MiCA regulation is intended to protect European investors from. Poland is still delaying implementation.

On a Thursday morning in December, in a federal courtroom on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan, Do Kwon stood before Judge Paul A. Engelmayer in a yellow prison jumpsuit. The thirty-four-year-old South Korean entrepreneur, once celebrated as a visionary of decentralized finance – a man whose followers called themselves “LUNAtics” and whose combined cryptocurrency holdings had briefly exceeded fifty billion dollars in market value – had spent months reading letters from his victims. Hundreds of them had written to the court in anticipation of this moment: retirees who had lost their savings, small-business owners who had trusted him with their futures, parents whose children’s college funds had evaporated in a matter of days.

“All of their stories were harrowing,” Kwon told the judge. “I want to tell these victims that I am sorry.”

The apology came three and a half years after the spectacular collapse of TerraUSD and Luna, the cryptocurrencies Kwon had created, which together vaporized some forty billion dollars in May 2022. It came after a global manhunt, an arrest in Montenegro while Kwon was traveling on a fraudulent Costa Rican passport, and a guilty plea in which he admitted to deceiving investors about the fundamental mechanics of his financial empire. And it came, finally, with a sentence: fifteen years in federal prison.

“This was a fraud on an epic, generational scale,” Judge Engelmayer said from the bench. “In the history of federal prosecutions, there are few frauds that have caused as much harm as you have, Mr. Kwon.”

The ruling in the Kwon case comes at a crucial moment for the European — and Polish — crypto-asset market. The MiCA Regulation (Markets in Crypto-Assets) has been fully in force in the European Union since 2024, establishing a comprehensive regulatory framework for crypto-asset issuers and related service providers (see Cryptocurrency trading in the context of the MiCA Regulation). Meanwhile, in Poland, implementation of these regulations has stalled — in December 2025, President Karol Nawrocki vetoed the crypto-assets bill, arguing, among other things, that it would place an excessive burden on the industry. However, the story of Do Kwon and the collapse of Terra and Luna clearly shows the cost of a lack of regulation — and why arguments for ‘unfettered innovation’ in the cryptocurrency sector should give way to the need to protect investors.

The Deception

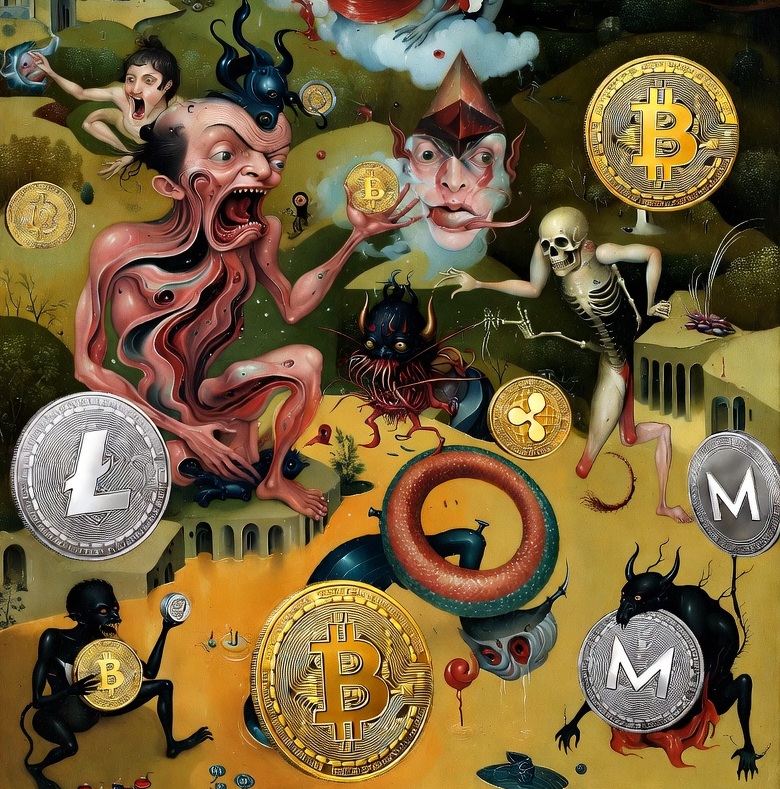

The story of Do Kwon is, in some respects, a familiar one – a tale of hubris, deception, and the eternal human appetite for easy money. But it is also something more particular: a parable about the collision of technological utopianism and old-fashioned grift, about what happens when the language of revolution is deployed in service of fraud. Kwon did not merely steal from his investors; he seduced them with a vision of a new financial order, one in which traditional banks and their fees and their gatekeepers would be rendered obsolete. His products bore names that evoked the celestial – Luna, for the moon; Terra, for the earth – and his marketing materials promised nothing less than to “set money free for billions worldwide.”

The federal indictment against Kwon, a document of some eighty pages that reads like a comprehensive taxonomy of deception, alleged that nearly every aspect of this vision was a lie. The algorithm that supposedly maintained the stability of his flagship cryptocurrency did not work as advertised. The foundation he created to defend that currency was not independent, as he claimed, but rather a vehicle for misappropriating hundreds of millions of dollars. The synthetic-stock platform he touted as decentralized was secretly manipulated by trading bots that Kwon funded and controlled. And the Korean payment application he pointed to as proof of “real-world” adoption of his blockchain did not, in fact, use his blockchain at all – Kwon simply copied its transactions onto the chain to create the illusion of utility.

Behind the revolutionary rhetoric, in other words, was something depressingly conventional: a man who understood that in moments of speculative mania, the requirements for success have “nothing to do with the fundamentals of the business,” as his own co-founder once observed, but rather depend on a “convincing and lofty white paper” and a “deep network of big name partners.” Kwon had both. What he lacked, evidently, was what he himself once called the necessary “moral constitution.”

The Stanford Wunderkind

Kwon was born in Seoul in 1991 and displayed early aptitude for the kind of abstract thinking that Silicon Valley prizes. He studied computer science at Stanford University and, according to various accounts, worked briefly at Apple and Microsoft before returning to South Korea to pursue his entrepreneurial ambitions. In 2018, he co-founded Terraform Labs with Daniel Shin, a more established figure in the Korean tech scene. Their stated goal was nothing less than the reinvention of money itself.

The product at the center of Terraform’s empire was TerraUSD, known as UST – a “stablecoin” designed to maintain a steady value of one dollar. The appeal of stablecoins in the volatile world of cryptocurrency is not hard to understand: they promise the upside of digital assets without the stomach-churning price swings that make Bitcoin unsuitable for everyday transactions. Most stablecoins achieve this stability through a straightforward mechanism – they hold reserves of actual dollars, or dollar-denominated assets, to back each token in circulation.

UST was different. It was “algorithmic,” which meant that its stability was supposed to be maintained not by reserves but by a clever computer program and its relationship to a sister cryptocurrency called Luna. The theory, as Kwon explained it in countless interviews and promotional materials, went something like this: if UST’s price dipped below a dollar, traders would be incentivized to swap it for a dollar’s worth of Luna, which would be “burned,” or destroyed. This would reduce the supply of UST, pushing its price back up. If UST rose above a dollar, the process would work in reverse. It was, Kwon assured investors, an elegant, self-correcting system – one that required no central authority, no reserves, no trust in institutions.

“So Terra is different in the sense that it’s an algorithmic stablecoin,” Kwon said on a podcast in January 2021, “which means there are no reserves that are backing the stablecoin.”

The claim was central to Terraform’s marketing. In a YouTube video titled “How Does Terra Work?”, the company explained that it had “designed a machine” that would respond to any variation in UST’s price by “bringing its price back to the $1 peg.” The video concluded with an appeal to the idealism that animated so much of the cryptocurrency movement: “Much like the moon which stabilizes the earth’s rotation, LUNA and its stakers are essential to Terra’s stability. Join us on our mission to create a truly open and transparent monetary platform that no one controls, setting money free for billions worldwide.”

This was stirring stuff. It was also, according to federal prosecutors, almost entirely false.

The First Crack

The first sign that something was wrong came in May 2021, a full year before the final collapse. That month, UST began to lose its dollar peg, dropping at one point below ninety-two cents. Under the theory that Kwon had sold to investors, this should have triggered a wave of arbitrage trading that would restore the peg automatically. Instead, the algorithm proved wholly inadequate to the task.

The problem, which Kwon had never disclosed, was that his system had a built-in throttle. When the protocol experienced a high volume of redemption requests – when many people wanted to exchange UST for Luna at the same time – transaction fees increased dramatically, eventually reaching a point where it was no longer profitable to use the system. According to prosecutors, the Terra Protocol could handle only about twenty million dollars in redemptions before this throttle kicked in. For a stablecoin with a market capitalization in the billions, this was a fatal design flaw.

Kwon’s response to the crisis was not to acknowledge the problem, or to warn investors that the system he had sold them was less robust than advertised. Instead, according to the indictment, he reached a secret oral agreement with a high-frequency trading firm to prop up UST’s price through market manipulation. The trading firm purchased tens of millions of dollars’ worth of UST – not because it saw value in the token, but because Kwon had promised to accelerate the delivery of Luna tokens under an existing investment agreement. During one critical thirty-minute window on May 23, 2021, the trading firm accounted for more than ninety percent of UST purchases in a key market, placing orders at prices higher than the prevailing rate in an explicit effort to push the token’s value back toward a dollar.

It worked. Within days, UST had returned to its peg. And Kwon went on a publicity tour, claiming that the algorithm had performed exactly as designed.

“We’ve never had a stress test of this magnitude,” he said on a podcast later that month. “And I think what we’ve proved is that the Terra Protocol indeed does need a lot of, what has been up to now, purely theoretical assumptions. And that it can survive black swan events.” In another interview, he was asked directly whether Terraform participated in market-making to maintain UST’s peg. “We don’t really do much of that anymore,” he said – a statement that prosecutors characterized as “knowingly false and misleading.”

The internal reaction at Terraform was rather different. In messages revealed in the indictment, Kwon told an employee that if the trading firm had not propped up UST, Terraform might have been “fucked.” An internal employee manual from 2021 described the trading firm as “quietly one of the biggest players in crypto” and “the biggest on-chain market maker of UST and saved our ass in May this year.”

The Unsustainable Promise

The lie worked, for a time. Investors, reassured by the apparent resilience of UST during the May 2021 “stress test,” poured money into the Terra ecosystem. A significant driver of this growth was the Anchor Protocol, a lending platform within the Terra system that offered depositors an annual return of approximately twenty percent on their UST – a rate that, as Kwon was repeatedly warned, was unsustainable. Anchor paid out far more in interest to its depositors than it earned from its borrowers; it was able to offer such extraordinary returns only because Kwon was quietly diverting funds from other parts of his empire to subsidize them. By early May 2022, roughly seventy percent of all UST in circulation – nearly thirteen billion dollars – was parked in Anchor, earning interest that existed only because Kwon was willing to pay it.

The growth was extraordinary. Between May 2021 and May 2022, UST’s market capitalization increased from approximately two billion dollars to approximately eighteen billion. Luna’s market value rose from roughly five billion to nearly thirty billion. At its peak, the combined market capitalization of Terraform’s cryptocurrencies exceeded fifty billion dollars. Forbes Magazine had named Kwon to its “30 Under 30” list for Finance & Venture Capital in Asia in 2019; by 2022, he was one of the most prominent figures in the entire cryptocurrency industry.

Then, in May 2022, UST lost its peg again. This time, the market was nine times larger than it had been a year earlier. The secret arrangements that had rescued the system in 2021 were inadequate to the scale of the crisis.

“Unfortunately it wasn’t so simple this time,” one trader at the firm that had helped Kwon in 2021 wrote to colleagues, “compared to when about $100 million committed was enough to re-peg.”

The collapse was swift and total. As UST fell below a dollar, the algorithm began minting Luna at an exponential rate in a futile attempt to restore the peg, leading to hyperinflation of Luna and a “death spiral” that destroyed both tokens within days. On May 9, 2022, with the collapse already underway, Kwon tweeted: “Deploying more capital – steady lads.” The message became a meme of hubris and denial. Forty billion dollars evaporated. In South Korea alone, an estimated two hundred and eighty thousand people lost money.

The Decentralization Illusion

The indictment reveals a pattern of deception that extended far beyond the stablecoin mechanism. Almost nothing that Kwon told investors about Terraform’s products, it turns out, was true.

Consider Mirror Protocol, a platform Kwon launched in December 2020 that allowed users to create, buy, and sell synthetic versions of stocks listed on American securities exchanges. The appeal was straightforward: investors anywhere in the world could gain exposure to Apple or Tesla without going through traditional brokerages. Kwon marketed Mirror as fully decentralized – controlled by its users through a governance token called MIR, with no special privileges retained by Terraform.

“In order to maintain censorship resistance, Mirror is entirely decentralized from day 1,” Kwon tweeted on December 3, 2020. “TFL has no special owner / operator keys.”

This was false. According to the indictment, Terraform secretly maintained a large number of MIR tokens and used them to influence governance votes. The company also retained operator keys that Kwon had publicly disclaimed. Internal messages reveal that Terraform employees understood they were lying to the public. “Mirror isn’t decentralized,” one employee wrote in July 2021. It was “a fake it till u make it thing” designed to “provide the initial illusion to make em [investors] believers.” Another employee, after spending an hour on a cryptocurrency livestream claiming that Mirror was decentralized, wrote that he “need[ed] to pray for forgiveness and repent.”

The deception went deeper still. Mirror’s supposedly decentralized pricing mechanism – which was meant to keep the prices of synthetic assets aligned with their real-world counterparts through market incentives – did not work. Kwon secretly funded and operated trading bots, which Terraform referred to internally as “MM bots,” to manipulate prices manually. An internal document explained that if the bots were not used, “the mAsset may be highly unlikely to track its underlying asset accurately.” In other words, the decentralized system that Kwon sold to investors required constant, centralized intervention to function at all.

Kwon used over eighty-five million dollars’ worth of pre-mined tokens – the “Genesis Stablecoins” that he had programmed into the Terra blockchain at its creation – to fund this manipulation. He had told investors that these tokens would be used for ecosystem development and user incentives. Instead, they became a slush fund for fraud.

The Chai Charade

Perhaps the most brazen of Kwon’s deceptions concerned a Korean payment application called Chai. From the beginning of Terraform’s existence, Kwon had pointed to Chai as proof that the Terra blockchain had “real-world” applications – that it was not merely a speculative toy but a functioning financial infrastructure that processed billions of dollars in transactions for millions of users. This was, as Kwon well knew, critical to his pitch. If Chai was using the Terra blockchain, then investors who “staked” their Luna tokens – locking them up within the system – would earn fees from those transactions. The more transactions, the higher the rewards.

“CHAI’s unique value proposition is enabled by Terra’s cutting-edge blockchain technology,” Kwon said in a presentation to CNBC in October 2019. Promotional materials claimed that Chai could settle transactions in six seconds, rather than the multiple days required by traditional payment processors, because it ran on the Terra blockchain.

In truth, Chai processed transactions through traditional bank rails operated by established financial institutions. It did not use the Terra blockchain at all. South Korean financial regulators, Kwon understood, would not issue electronic-payment licenses to companies that used cryptocurrency to process payments. So Kwon arranged for Chai to use conventional banking infrastructure to obtain those licenses – while simultaneously telling investors that Chai was a blockchain-based payments system.

To maintain the illusion, Kwon and his co-conspirators created an automated process that “mirrored” Chai’s transactions onto the Terra blockchain after the fact. When a customer made a purchase through Chai, the transaction was processed through normal banking channels; separately, a small amount of stablecoin was transferred between wallets that Kwon controlled, creating the appearance of blockchain activity. Over time, these methods grew more sophisticated, with fake patterns of transactions designed to make some wallets appear to belong to sellers and others to buyers. Kwon used over sixty million dollars’ worth of the Genesis Stablecoins to fund this elaborate fiction.

The deception required constant management. When a Korean news website reported in June 2019 that Chai did not actually use stablecoins, a Terraform employee attempted to have the article revised. The editor refused. “Given that [the editor] even hinted that she knows we chose this path due to reg risks,” the employee wrote to Kwon, “I think we should let it be.”

Internally, Terraform employees understood that they were telling different lies to different audiences – one story to investors, another to regulators. “My dilemma is that [at the moment], as Do pointed out, we are not being honest with the media,” one employee wrote to Kwon’s co-founder in June 2019. If certain financial arrangements were disclosed, “we’d be put in an awkward situation where we have lied to the banks, to whom we promised both verbally and in writing that CHAI has nothing to do with Terra/cryptocurrency.”

Even after Terraform and Chai formally separated their business operations in March 2020, Kwon secured a written agreement allowing him to continue representing Chai transactions as taking place on the Terra blockchain. His co-founder later described this to a colleague as a “look the other way” agreement. When that colleague expressed concern about the “fraudulent” narrative, the co-founder responded: “It does bother me somewhat morally that the narrative is off. But that’s not – I don’t think [it’s] your problem, and I think it’s not necessarily my problem either. I think it’s Do [Kwon]’s problem.”

The Foundation That Wasn’t

After the May 2022 collapse, Kwon created yet another fiction to cover his tracks. In January 2022, he had announced the formation of the Luna Foundation Guard, or LFG – a supposedly independent body governed by a council of industry experts that would maintain billions of dollars in reserves to defend UST’s peg. The LFG, Kwon told investors, represented a “counterweight” to Terraform, a decentralized safeguard against exactly the kind of crisis that had threatened the system in May 2021.

“The LFG is governed independently by an international Council of industry leaders and experts,” Terraform tweeted in January 2022. In a podcast interview two months later, Kwon claimed that the approximately three billion dollars’ worth of bitcoin held in the LFG Reserve was secured in “multisig” wallets controlled by the governing council – wallets that would require multiple private keys to authorize any transaction.

None of this was true. According to the indictment, internal corporate records show that Kwon established the LFG Governing Council only as a “non-director subcommittee” whose powers were limited to giving advice and recommendations. The LFG was legally governed by a two-person board consisting of Kwon himself and a Singaporean business consultant who had been appointed solely to satisfy local regulations and exercised no independent judgment. The reserves were not held in multisig wallets controlled by the council, but in wallets controlled by Kwon personally.

When UST collapsed in May 2022, Kwon spent over eight hundred million dollars’ worth of LFG bitcoin without any vote from the governing council. After one council member learned of this and told Kwon that “I think it’s important to highlight that most of these [LFG Reserve] transactions were executed without a vote,” Kwon responded: “With the community and every media outlet out with pitchforks not sure if its the best time to throw me under the bus.”

But Kwon’s manipulation of the LFG did not stop there. After the crash, he engaged in what prosecutors described as “retroactive accounting tricks” to benefit himself at the expense of investors. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of LFG assets remained after the failed defense of the peg. Rather than returning these funds to the LFG or to investors, Kwon directed that they be transferred to Terraform as “reimbursement” for earlier spending – spending that had occurred before the LFG funds were even deposited into the relevant account. To justify this maneuver, Kwon reverse-engineered the company’s accounting, selecting a period of time during which Terraform had spent approximately one billion dollars defending the peg and attributing all of that spending to the LFG after the fact.

In other words, Kwon used creative accounting to shift losses from Terraform to the LFG, allowing Terraform to keep over three hundred million dollars in bitcoin that should have belonged to investors. These “Misappropriated LFG Funds” made up most of Terraform’s remaining assets after the crash.

Kwon then commissioned a consulting firm to produce an “audit report” that he promoted as providing “full transparency” into the LFG’s activities. The report, which Kwon described as independent, was anything but. An internal email from the consulting firm noted that one of Kwon’s agents had “dictated those paragraphs to us.” The report omitted the unauthorized spending, the retroactive accounting, and the fact that Kwon had used LFG funds in ways that substantially benefited himself.

The Fugitive

As government investigations began in multiple jurisdictions, Kwon made public statements about being in “full cooperation” with law enforcement. In truth, according to the indictment, he was doing the opposite. In a recorded conversation with an associate in August 2022, Kwon explained his strategy: his approach to law enforcement, he said, was to “tell them to fuck off.” He claimed to be seeking “political protection” from countries without extradition treaties with the United States, and said he was “pretty comfortable” that he would never face criminal charges.

Kwon fled, first to Singapore, then to Serbia, and finally to Montenegro. He moved the Misappropriated LFG Funds through a complex series of transactions designed to conceal their origin – transferring them through multiple cryptocurrency addresses, “bridging” them between different blockchains, and routing them through centralized exchanges within short windows of time to obscure their trail. Tens of millions of dollars were ultimately transferred to a Swiss bank account held by Terraform; from there, they were used to pay professional services fees and expenses for Kwon and his company.

When public reporting revealed that significant funds had been routed through the cryptocurrency exchanges KuCoin and OKX, Kwon denied it publicly. “I havent used kucoin or okex in at least the last year,” he posted on social media in September 2022. “I don’t even use Kucoin and OkEx,” he wrote a week later. In an interview the following month, he said: “I really have not used, you know, KuCoin or OKX or done any trading on those platforms, at least as far as I can remember.”

These statements were false. Both accounts had been opened in Terraform’s name, with copies of Kwon’s passport submitted as part of the exchanges’ identity-verification procedures. In the days following South Korea’s announcement of criminal charges against him, Kwon had routed approximately sixty-six million dollars through these accounts.

On March 23, 2023, Kwon was arrested at the Podgorica airport in Montenegro. He was attempting to board a flight to the United Arab Emirates using a forged Costa Rican passport. After months of legal wrangling between the United States and South Korea, both of which sought his extradition, he was sent to New York, where he arrived on December 31, 2024.

The Reckoning

Among those who wrote to Judge Engelmayer was Ayyildiz Attila, who described losing between four hundred thousand and five hundred thousand dollars in the collapse. “My savings, my future, and the results of years of sacrifice disappeared,” he wrote. “I struggled to keep up with payments and responsibilities, and everything I had worked for was erased.”

The letters, taken together, tell a story of ordinary people – retirees, small-business owners, parents saving for their children’s education – who trusted a man who told them he had discovered a new and better form of money. They were drawn in by the promise of stability, by the high returns offered by Anchor, by Kwon’s confident assertions that his system had been tested and proven. Many of them had done their due diligence, or what they understood due diligence to mean in the bewildering world of cryptocurrency. They read the white papers. They watched the interviews. They believed.

This is what makes Kwon’s fraud particularly poignant, and particularly galling. He did not merely take advantage of greed; he exploited hope. The vision he sold – of a financial system freed from the predations of banks and governments, accessible to anyone with an internet connection – is not, in itself, a contemptible one. It is a vision that has animated serious thinkers and engineers for more than a decade. But Kwon perverted that vision, using the language of decentralization and algorithmic elegance to obscure what was, in the end, a very old-fashioned scheme: promise what you cannot deliver, cover up the failures, and hope that you can stay ahead of the collapse long enough to escape with the proceeds.

What Remains

Kwon’s sentencing brings to a close one chapter of the cryptocurrency industry’s reckoning with the excesses of 2022. He joins a growing roster of crypto executives who have faced federal charges in the aftermath of that year’s market collapse: Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder of FTX, was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for fraud and conspiracy; Alex Mashinsky, the founder of the lending platform Celsius, pleaded guilty to fraud charges. The industry that once promised to operate beyond the reach of regulators has discovered, to its apparent surprise, that the laws against fraud apply to tokens as surely as they do to stocks and bonds.

Whether these prosecutions will reshape the cryptocurrency industry in any lasting way remains to be seen. The believers remain believers. Bitcoin has continued its volatile climb. New tokens proliferate. And somewhere, no doubt, another entrepreneur is working on the next algorithmic stablecoin, the next decentralized lending platform, the next financial instrument that will finally deliver the utopia that the old ones merely promised.

As for Kwon, he will serve his time – or at least half of it, before he may apply for transfer to South Korea to face additional charges there. In a statement after the sentencing, his lawyer said that Kwon “spoke from the heart” and “expressed genuine remorse.”

Perhaps he did. But the passage from the indictment that lingers in the mind comes from the very beginning, before Terraform had launched, before the billions had flowed in, before the collapse and the manhunt and the forged passport. In January 2018, Kwon exchanged emails with his co-founder about the cryptocurrency market. The co-founder observed that it “[a]lmost seems like a huge ginormous bubble that we should somehow partake in before it crashes.” Kwon responded that there were “good returns to be had” on different kinds of cryptocurrency projects, “depending on your risk appetite / moral constitution ;).”

The winky face, in retrospect, tells you everything you need to know.

Seven years later, in a yellow jumpsuit in a federal courtroom, Kwon learned the price of the choice he had made. Judge Engelmayer, in passing sentence, noted that the case was distinguished not only by the scale of the losses but by the “pervasiveness and persistence” of Kwon’s deceptions. From the beginning – from the very first emails about a stablecoin whose stability, Kwon himself acknowledged, “has not been proven” – he had understood the risks and chosen to conceal them. He had built his empire on lies, sustained it with manipulation, and fled when it collapsed.

Fifteen years. For the victims, it will never be enough. For the industry, it may serve as a reminder that the old rules still apply, even in the new world of decentralized finance. And for Kwon himself – the Stanford computer scientist, the Forbes “30 Under 30” honoree, the self-styled crypto king – it marks the end of a journey that began with a question about moral constitution and ended with an answer delivered by a federal judge.

The moon, it turns out, could not stabilize Terra after all. ♦

Founder and Managing Partner of Skarbiec Law Firm, recognized by Dziennik Gazeta Prawna as one of the best tax advisory firms in Poland (2023, 2024). Legal advisor with 19 years of experience, serving Forbes-listed entrepreneurs and innovative start-ups. One of the most frequently quoted experts on commercial and tax law in the Polish media, regularly publishing in Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Author of the publication “AI Decoding Satoshi Nakamoto. Artificial Intelligence on the Trail of Bitcoin’s Creator” and co-author of the award-winning book “Bezpieczeństwo współczesnej firmy” (Security of a Modern Company). LinkedIn profile: 18 500 followers, 4 million views per year. Awards: 4-time winner of the European Medal, Golden Statuette of the Polish Business Leader, title of “International Tax Planning Law Firm of the Year in Poland.” He specializes in strategic legal consulting, tax planning, and crisis management for business.